Jackie had already left for Ebbets Field when Rachel packed up five-month-old Jackie Jr. and his baby gear and hailed a cab for Brooklyn. It was April 15, opening day of the 1947 Major League Baseball season and Jackie’s first day in uniform as a Brooklyn Dodger. Jackie Jr. was getting over a bout of diarrhea, but after all they had been through so far, Rachel was determined not to miss the opening game.

At the stadium, Rachel ran around to find a hot dog Vendor who would warm Jackie Jr.’s formula. Then she sat behind the Dodger dugout and immediately realized that the infant was inadequately dressed for the nippy day.

Luckily she was sitting next to catcher Roy Campanella’s mother-in-law, who snuggled the five-month-old inside her fur coat. That done, Rachel sat down to watch her twenty-eight-year-old husband make history.

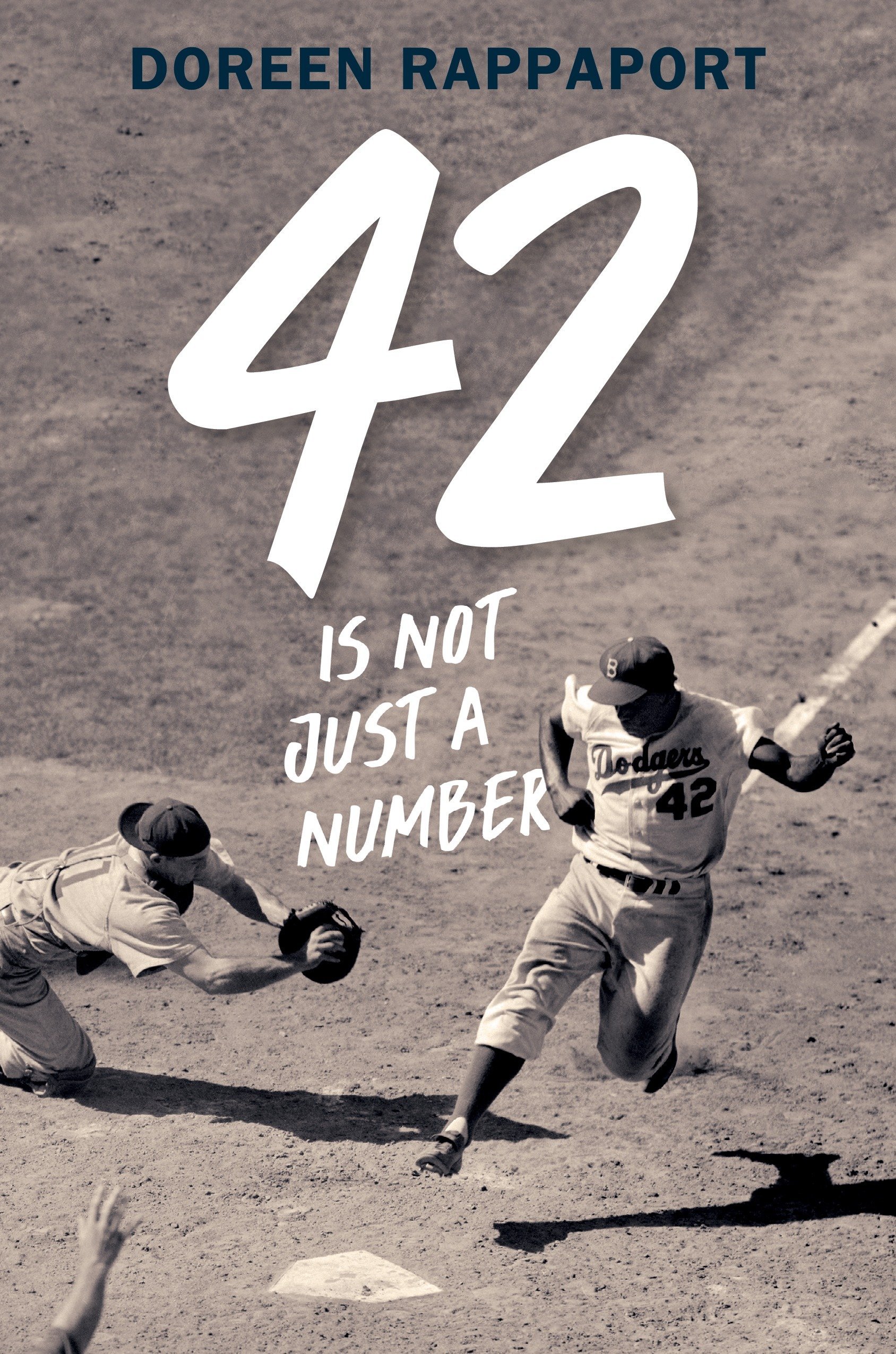

Just shy of six feet tall, Jackie weighed 195 pounds. His shoulders seemed broad in comparison to his thin legs. His cap shielded his face from view, but the number on the back of his cream-and-blue flannel uniform — 42 popped for all to see. Rachel didn’t have to see Jackie’s face to know how he felt about this moment. He had excelled with the Montreal Royals. Now came the big test, the one he could not afford to fail. It was a heavy weight to carry.

Cheers filled the stadium whenever Jackie came up to bat. In the first, third, and fifth innings, he didn’t get a hit. In the bottom of the seventh, with the Dodgers trailing the Boston Braves, 3-2, Eddie Stanky, the Dodgers’ second baseman, got on first with a walk. Jackie followed with a perfect sacrifice bunt, beat out the throw to first, and sailed to second on an error by the Braves’ first baseman. Stanky advanced to third. Then Pete Reiser hit a double; Stanky and Jackie ran home, putting the Dodgers ahead, 4-3. Gene Hermanski drove in another run to clinch the win.

In his first week, Jackie played four games, got six hits out of fourteen times at bat, scored five times, and made thirty-three putouts without an error.

What Jackie did not know was that before the regular season had even started, some of his teammates had drawn up a petition to keep him off the team. Most Dodger players were southern born and bred. Rickey knew how deeply ingrained their prejudice was, but he had no intention of tolerating racism. In private meetings, he told each petitioner that only he decided who played for the Dodgers. If someone didn’t want to play with Jackie, Rickey would gladly trade him. Rickey was willing to lose even Dixie Walker, the team’s leading hitter and most popular player.

“Bench jockeying” is a baseball tradition in which opposing teams shout insults at each other. Rookies got the worst of it, but no one was prepared for the vicious racial epithets thrown at Jackie on April 22, when the Philadelphia Phillies came to Ebbets Field. The Phillies’ manager, Alabama-born Ben Chapman, had specifically instructed his players to taunt Jackie. It was common knowledge in the sports world that Jackie had promised Rickey that he would not respond to any attacks. From Jackie’s first at bat to the end of the game, venom spewed from the Phillies dugout.

Jackie’s teammates knew the constant pressure he was under, and they witnessed his dignity and courage in facing it. Pitchers were still intentionally hitting him. The abusive language had not stopped, but still he kept focused on the game. Even though Jackie and a grand mission, he wasn’t out for personal glory. When he stole bases, it was to win, not to rack up statistics and applause. He was a team player. His incredible talent was helping move the team toward capturing the National League pennant. He had earned their respect and gratitude. Now he was invited to join in the banter and card games, but still, there was no player he could really call a friend.

He was welcomed in Pittsburgh, Boston, and Chicago hotels, but he was still barred from the Benjamin Franklin Hotel in Philadelphia and all hotels in St. Louis. Cincinnati, Netherland Plaza now agreed to let him stay, but wouldn’t let him eat in the hotel restaurant or swim in its pool. Not one teammate objected on his behalf. No player ever invited him to go out to eat somewhere else. Most nights he ate alone or with Wendell Smith.

On the playing field, the racist taunts had not stopped. In St. Louis, on July 29, as hateful words echoed around the Cardinals’ stadium, Jackie’s fans came to his defense. Black spectators were the first to stand up and applaud him. Soon whites were standing and cheering him on, too. The whistling and shouting got so loud that it drowned out the jeering and the vile language. As heartening as his fans’ support was, it could not erase Jackie’s persistent aloneness.

When he was home in Brooklyn with Rachel and Jackie Jr., love surrounded him, but the tension inside him never completely disappeared. Black Americans were depending on him to succeed, to show the white world that they were equally talented if given the chance. It was an overwhelming and constant burden. It disturbed his sleep. Oftentimes it made him uncommunicative.

Branch Rickey had been right when he told Jackie that he would need a good woman by his side. Rachel was that loving, understanding woman. She knew not to probe, to give him room to be silent and to and reflect. She was there, waiting patiently to listen whenever he was willing to talk. He was a lucky man.

Comprehension Questions

1. Who were the main supports for Jackie while he played baseball in 1947?

A. All of his Brooklyn Dodger teammates were his friends.

B. The Brooklyn Dodger's team president, Branch Rickey and his wife, Rachel were his main supports.

C. Ben Chapman supported him, especially in Philadelphia.

A. He believed that baseball could be racially integrated.

B. He wanted the glory and the money he earned.

C. He like to pick fights.

Your Thoughts

Vocabulary

4. List any vocabulary words below.