CAN BAD LUCK FOLLOW A PERSON FOREVER? June Yang had always believed there was a cosmic distribution of fortune by which everyone had equal amounts of good and bad luck in their lives. But here June was, miles away from home, standing in front of a drab, used-to-be-white building with her viola strapped to her back and a black garbage bag next to her filled with everything she owned in the whole world. Her theory about luck must be wrong, because it seemed as if she had had enough bad luck for two lifetimes.

“What is this place?” asked Maybelle, her little sister.

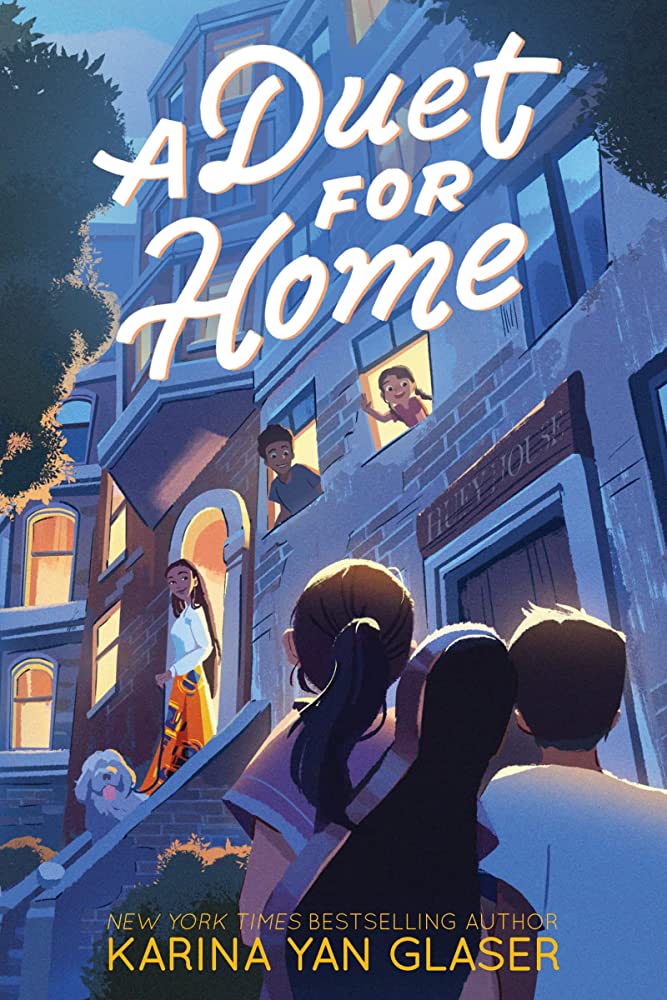

June didn’t answer. She stared up at the building. The entrance had a crooked sign nailed over the entrance that said HUEY HOUSE.

Maybelle, who was six years old, wore multiple layers of clothes on that unseasonably warm September afternoon: several pairs of underwear, leggings under her jeans, two T-shirts, three long-sleeved shirts, a sweater, her puffy jacket, a scarf, winter hat, and sneakers with two pairs of socks. If she fell over, she might roll down the street and disappear forever. June admired Maybelle’s foresight, though. By wearing nearly every item of clothing she owned, she had freed up room in her garbage bag for the things she really could not live without: her books (all about dogs) and stuffed animals (also all dogs).

Maybelle really liked dogs.

“Is this like jail?” Maybelle continued, poking the bristly hairs from the bottom of her braid against her lips. “Did we do something really bad? When can we go home again?”

June put on her everything will be just fine! face. “Of course it’s not jail!” she said. “It’s an apartment building! We’re going to live here! It’s going to be great!” Then she reached up to grab the straps of her viola case, reassuring herself it was still there.

“It looks like a jail,” Maybelle said dubiously.

June gave the building a good, hard stare. Even though it appeared sturdy, it seemed. . . exhausted. There were lots of concrete repair patches on the bricks, and some of the windows were outfitted with black safety bars. The door was thick metal with a skinny rectangle of a window covered by a wire cage, just like the windows at school.

It did look like a jail, but June wasn’t going to tell Maybelle that.

She glanced at her mom, but June already knew she wouldn’t have anything to say. Mom had stopped talking about six months ago, right after the accident.

“June, where are-” Before Maybelle could finish her sentence, the metal door of the building creaked open. A man-his head shaved, two gold earrings in the upper part of his ear, and wearing a black T-shirt -emerged and stared down at them from his great height. He looked like a guy who belonged on one of those world wrestling shows her dad would never let them watch. Maybelle shrank behind her, and Mom stood there still and quiet, her face blank and unreadable. June referred to this as her marble-statue face. Once, on a school field trip, June had gone to a fancy museum and there was a whole room of carved marble heads, their unemotional faces giving nothing away.

“You guys coming in?” the man asked, jamming a thumb toward the building.

June fumbled in her jeans pocket for the piece of paper the lady at EAU, or the Emergency Assistance Unit, had given her. The marshal, who delivered the notice of eviction, had instructed them to go to the EAU when June told him they had nowhere else to go.

June had packed up all their stuff while Maybelle cried and Mom shut herself in her bedroom. After checking and double- checking directions to the EAU (June had had no idea what that was), she’d managed to pack their things into three black garbage bags. She told Maybelle that they were going to a new home but then immediately regretted it when her sister wanted to know all the details: Was it a house or an apartment? How many bedrooms did it have? Was the kitchen large?

That was last night. Other than a funeral home, the EAU was the most depressing place June had ever been. After filling out a stack of forms and spending the night in the EAU hallway, which they shared with three other families and buzzing fluorescent lights, June had been told by the lady in charge to come here. Staring at the building and hoping it wasn’t their new home, June crossed her fingers and begged the universe to have mercy on them.

The universe decided to ignore her, because the man said, “The EAU sent you, right? First-timers?”

June nodded, but her stomach felt as if it were filled with rocks.

“I’m Marcus,” he said. “Head of security here.”

Security? Maybelle moved even closer to June while Mom maintained her marble-statue face.

Marcus pointed to June’s viola case. “You can’t bring that inside. It’ll get confiscated in two seconds.”

June wrapped her fingers around the straps so tightly she could feel her knuckles getting numb. “It’s just a viola,” she said, her voice coming out squeaky.

“Exactly. Instruments aren’t allowed.”

June tried to look strong and confident, like her dad would have wanted her to be. “There’s no way I’m letting you take this away from me.” After all, the viola was the only thing Dad had left her. It was equal to over two years of his tip money. Even after so many months, June could picture him as if he were still with them. Dad making delivery after delivery through congested and uneven Chinatown streets, plastic bags of General Tso’s chicken and pork dumplings hanging from his handlebars. Dad riding his bike through punishing snowstorms because people didn’t want to leave their house to get food. Dad putting the tip money into the plastic bag marked VIOLA in the freezer at the end of every shift, his version of a savings account.

Maybelle, still hiding behind her, called out, “June’s the best eleven-year-old viola player in the world.”

“That’s not true,” June said humbly, but then she wondered if Marcus thought she was going to play awful music that drove him bananas. She added, “But I’m not, like, a beginner or anything. No one had a problem with me practicing in our old apartment. And I play classical music. Mozart and Vivaldi and Bach.” She felt herself doing that nervous babble thing. “I can also play Telemann if you like him. He lived during Bach’s time…”

Marcus’s mouth stayed in a straight line, but she could tell he was softening.

After a long pause, he spoke. “I can hide it in my office. If you bring it inside and she sees you with it, she’ll throw it out.”

June swallowed. What kind of monster would throw away an instrument? And how could she be sure that Marcus wouldn’t run off with it?

“I promise to keep it safe,” he added simply.

June felt Maybelle’s skinny finger stick into her back. “You’re not really going to give it to him, are you?”

June never let anyone touch her instrument, ever. Maybelle had known that rule the moment June showed her the viola for the first time. But what choice did June have now? It was either trust a stranger with her viola or lose it forever.

She handed the viola case over, her skin prickling with a thousand needles of unease.

Comprehension Questions

1. Who gave June her viola?

A. Her mom

B. Her grandma

C. Her dad

A. She didn't want him to play it

B. It was the only thing her dad had left her

C. She doesn't want him to sell it

Your Thoughts

Vocabulary

4. List any vocabulary words below.