Ba-ba always told me I was a miracle. Because, technically, I was. His doctor had said it was impossible for him and Mom to have children due to his cancer treatments. I wasn’t supposed to exist. He was never supposed to meet me.

Most of the time, I felt like a miracle because I could figure out Ba-ba’s mood and help him feel better. But some- times I had a deep-down feeling that Ba-ba was the actual miracle.

“I want to talk to you today about the hope,” Ba-ba said, pretending he was speaking to a large crowd of elementary school students and teachers.

Near the beginning of the year, in early August, my school held a one-mile walk/run fundraiser and donated the money to the National Foundation for Cancer Research in Ba-ba’s honor. He wanted to thank everyone in person, so my school had scheduled a visit. But he’d gotten a fever the night before and had been in the hospital for four days now.

“Leave the the out,” I said. I was sitting beside him in a padded pink chair.

He shifted in his hospital bed. The fluorescent lights from overhead glared through his thinning hair. “I want to talk to you today about hope. How it is essential-”

I nodded. “Good, you remembered the l sound.” “in a life of adversity, like mine. But even though I have had the lifetime of ”

“A lifetime,” I interrupted.

He blew out a breath and started over, like a frustrated orchestra conductor. But the strains of his prelude didn’t mess up the next run-through. He didn’t make any more mistakes, not for ten whole minutes. No mixed-up r‘s and l’s, or switching he and she, or having his halting rhythm. He even made it through his favorite Emily Dickinson poem, about the bird braving the storm and wind and sea, but always surviving. And he did all of it while ignoring the blips on his monitors.

“Amie.” Mom popped into the room and closed the door, shutting out the chatter of nurses. “We should go for dinner in the cafeteria.”

“Okay. Just five more minutes.” Ba-ba was only partway through his speech.

Mom sighed and took her phone out as she went into the bathroom. Her rubber soles squeaked on the tile.

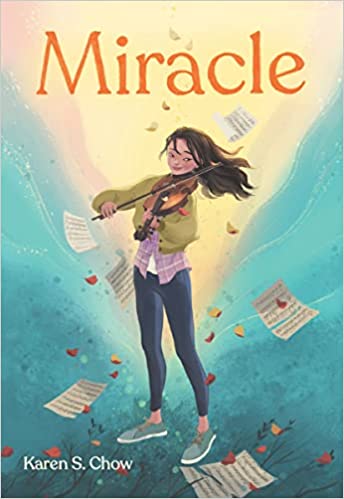

“Some days,” Ba-ba continued, “it takes more than mental strength to keep me hopeful. Some days, I will be reminded by my daughter and her beautiful violin. Her music has always been able to lift me in spirit.”

I knew every word of his speech and still got embar- rassed when he mentioned me.

He listed his low-hope moments when he lost all his hair from chemotherapy when I was four, and also mentioned the two times when I was six that he almost died because he couldn’t stop vomiting.

Mom emerged from the bathroom. “Ready?”

“Just a second. We’re at the last part.” I placed my hand on Ba-ba’s hospital-white bed. “Keep going.”

Ba-ba took a sip of water, cleared his throat, and pro- jected to the audience of muted TV news anchors on the wall. “I have been in and out of hospitals more times than I can remember. I have taken many, many tests, more than all your spelling tests combined.”

I smiled.

“I have had thousands of shots and taken thousands of medications…”

Mom sighed loudly from the doorway.

“…but it is simply a list of what sickness can cause,” Ba-ba continued, glancing at her. “Sickness may be a life- style, but it does not need to be an entire identity.”

Mom cleared her throat. Her eyebrows were low, and her mouth a firm line. “Amie.”

“Ba-ba’s last paragraph,” I said.

“Ba knows that he will probably not speak to your school like we planned. His fever was too severe, and I do not want to risk him getting more germs.” She folded her arms. “I wish you would both stop hoping.”

I gazed at Ba-ba. He cast his eyes to the cream-colored blanket covering his hands, IV tube, and heart-rate monitor.

“We need to get something to eat,” Mom said softly.

“The cafeteria is closing.”

I reached to squeeze Ba-ba’s hand and whispered the last line of his speech: “Do not give up.”

Ba-ba’s face crinkled into a smile.

“See you soon.” I squeezed his hand again, and this time he squeezed back. My head filled with pops of happy music-more specifically, Mozart.

As I left the room, I barely noticed the bustle of nurses and doctors, the announcements over the speakers, or the other patients being wheeled down the halls. I could only think of Ba-ba. My heart was so full, it swelled. Sure, his body was battling an infection on top of his cancer. Sure, his cancer had been winning for the last four days. But he was always bold, fighting for what he wanted even while sick. He was brave, facing his treatments and disappointments. He was hopeful for the very best. He was the real miracle, and I was simply his praise song.

Comprehension Questions

1. When did Amie's school have a one-mile walk/run fundraiser for the National Foundation for Cancer Research?

A. Around the star of spring, in late March

B. Near the beginning of the year, in early August

C. In June right after school was done

A. He was sick enough and she did not want him to catch anything else

B. The school play was at the same time

C. The doctor said it would be better if he did not go

Your Thoughts

Vocabulary

4. List any vocabulary words below.