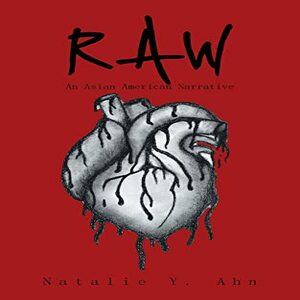

Here Is My Beginning,

Head down, sunglasses and mask on, baseball cap pulled low, I grabbed what was on the grocery list from my mother as quickly as possible. My father’s voice echoed in my mind as I sped through the produce section. Don’t stay longer than you have to.

The first wave of the pandemic back in March 2020 brought Asian xenophobia into full throttle. Even in my small Caucasian town, I was noticing strange interactions. Whether it was the disapproving shake of a head or a full-on racial slur, it incited fear in me I couldn’t shake. And this proved to be difficult to ignore when I was consistently the only Asian person in the room. I was a child again—kids were stretching their eyes sideways at me, singing ching chong in accented voices, laughing at the food I brought for lunch. I was “ugly”; “smelly”; and, worse, an outsider.

In seventh grade, I was assigned a family tree presentation. I interviewed my grandmother and grew excited over the stories she told about our family, who created a soybean milk company to get protein to lactose-intolerant children, reforested the Korean Peninsula after the war, and built schools. I stayed up perfecting my poster, carefully cutting and pasting pictures, and ironing my traditional Korean hanbok. For the first time, I was excited to talk about my family.

But the other presentations were about white families on big Southern porches with family crests embossed onto their giant door knockers. I felt silly next to those photos in my dress. My ears started ringing and cheeks started to burn. The colors suddenly looked gaudy and childish; the rainbow sleeves too loud—not at all like the intricate silk tapestry I had spent hours ironing the night before. I took off my jade headpiece and stuffed it into my bag.

I presented as quickly as possible, rushing through the details, leaving out my favorite parts to just get it over with. My shame rushed back—my three-generation household, missing out on “normal” weekends because of Saturday Korean school, my slanted eyes, my grandmother’s inability to speak English. I wanted so badly to be the same as everybody else.

So I taped my eyes so they would appear larger, dyed my hair, and changed what I wore. I stopped attending Korean school and bought cafeteria lunches. I made the friends I longed for but still felt out of place. No matter how much I changed, I was never quite “right” enough to slide into place and fit in. Chronically inadequate—a feeling that no amount of flavored lip gloss could fix. I was still the little girl who was too afraid to eat her lunch in front of her classmates.

Comprehension Questions

1. Who did the narrator interview for her family tree project?

A. Her dad

B. Her grandfather

C. Her grandmother

A. They made fun of how she ate her food

B. They made fun of how her food looked and smelled

C. They made fun of her having to buy school lunch

Your Thoughts

Vocabulary

4. List any vocabulary words below.